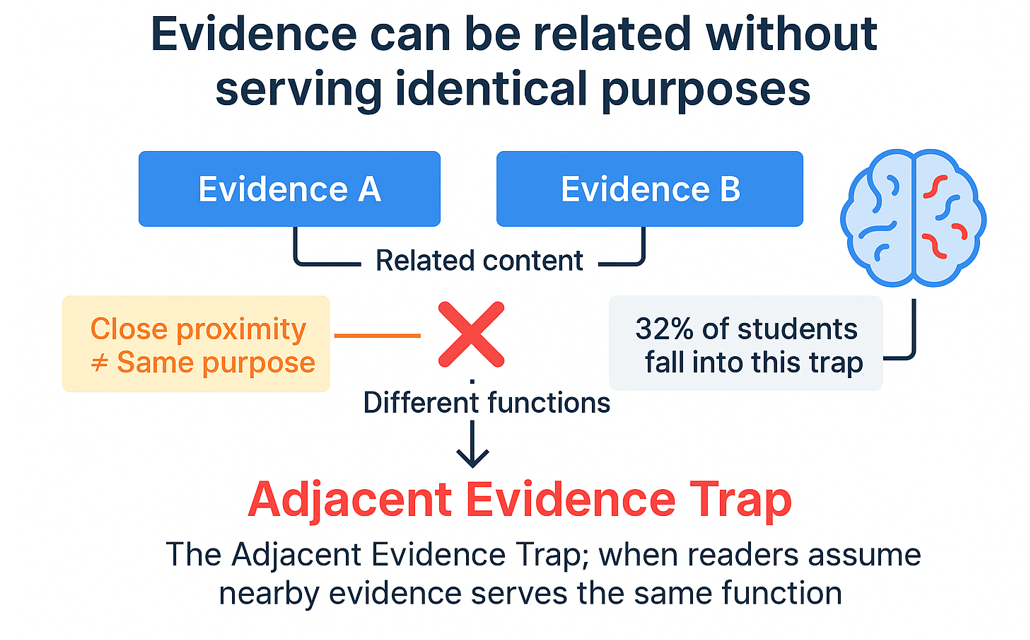

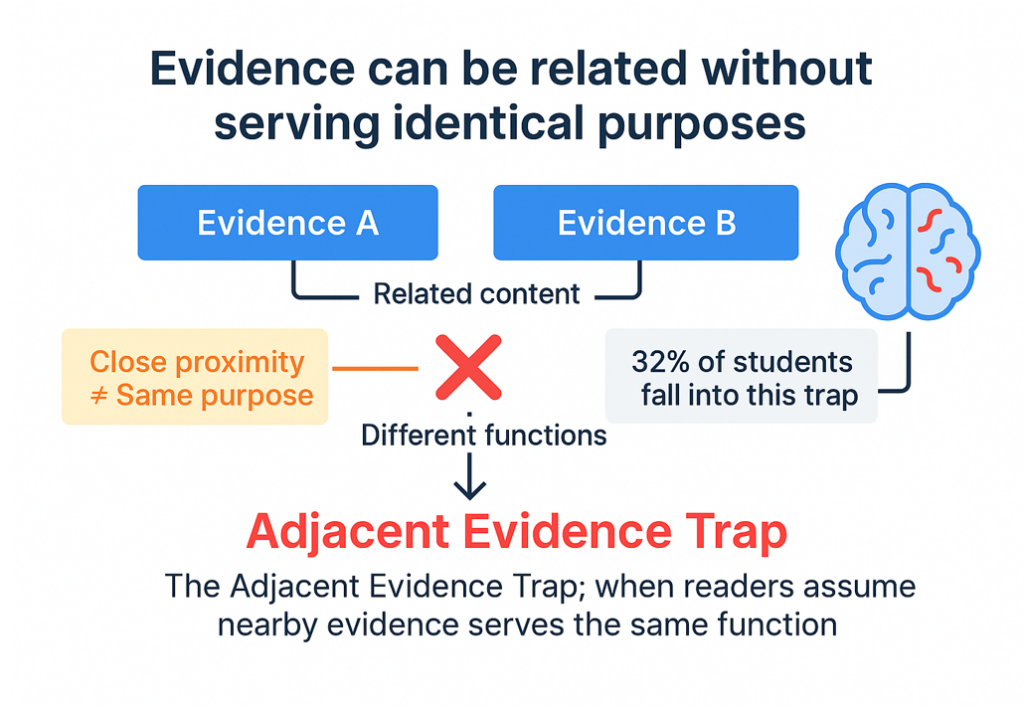

Every day, skilled readers make a subtle but costly mistake in RC: they assume that evidence appearing near each other in a passage serves the same function. It’s an intuitive error—after all, don’t authors group related information together? Yes, but here’s the crucial distinction: evidence can be related without serving identical purposes.

This misunderstanding costs test-takers dearly on RC function questions, where approximately one-third of students fall into what we call the “Adjacent Evidence Trap.”

Key Takeaways About the Adjacent Evidence Trap:

The Adjacent Evidence Trap is one of the most common mistakes in GMAT RC function questions. Here’s what you need to know:

- What is it? Assuming that evidence appearing close together serves the same function

- Why it happens: Our brains naturally associate nearby information with similar purposes

- The impact: Approximately 32% of test-takers fall into this trap on function questions

- The solution: Use systematic Evidence Function Analysis to identify distinct purposes

This guide provides a proven framework to avoid this trap and master RC function questions.

⭐MASTER RC WITH PROVEN STRATEGIES

Access our Free GMAT RC Resources including detailed strategy guides, practice questions, and video lessons. Start building the skills that top scorers use to dominate Reading Comprehension.

The Core Problem: Conflating Proximity with Purpose

Consider how a skilled attorney builds a case. First, they present evidence to establish a fact: “The defendant was at the scene.” Then, they add supplementary evidence: “Moreover, beyond just being present, the defendant also had motive and opportunity.” Both pieces of evidence relate to guilt, but they serve different functions—the first establishes presence, the second extends the argument to motive and opportunity.

GMAT passages work the same way. Authors layer evidence strategically: some evidence supports a main claim, while other evidence extends, qualifies, or adds nuance to that claim. The test exploits students’ tendency to treat adjacent evidence as functionally identical.

How This Appears in GMAT RC

According to our analysis of thousands of GMAT responses, approximately 32% of test-takers make this error on function questions, making it one of the most common traps in RC. Here’s why:

A Simple Example

Imagine reading this passage:

“Studies show regular exercise improves cardiovascular health. Research found that participants who exercised three times weekly showed 20% improvement in heart function. Additionally, beyond cardiovascular benefits, exercise improved sleep quality and mental clarity.”

Now answer: The author mentions the 20% improvement primarily to:

- A) Support the general claim about cardiovascular benefits

- B) Demonstrate health benefits beyond cardiovascular improvements

Many students choose B because they see the cardiovascular data near the sentence about “beyond cardiovascular benefits” and assume the 20% statistic is an example of those additional benefits. But read carefully: the 20% improvement IS a cardiovascular benefit. The “beyond cardiovascular” part comes in the next sentence and refers to sleep and mental clarity.

This is the Adjacent Evidence Trap in action.

Why Smart Test-Takers Fall for This

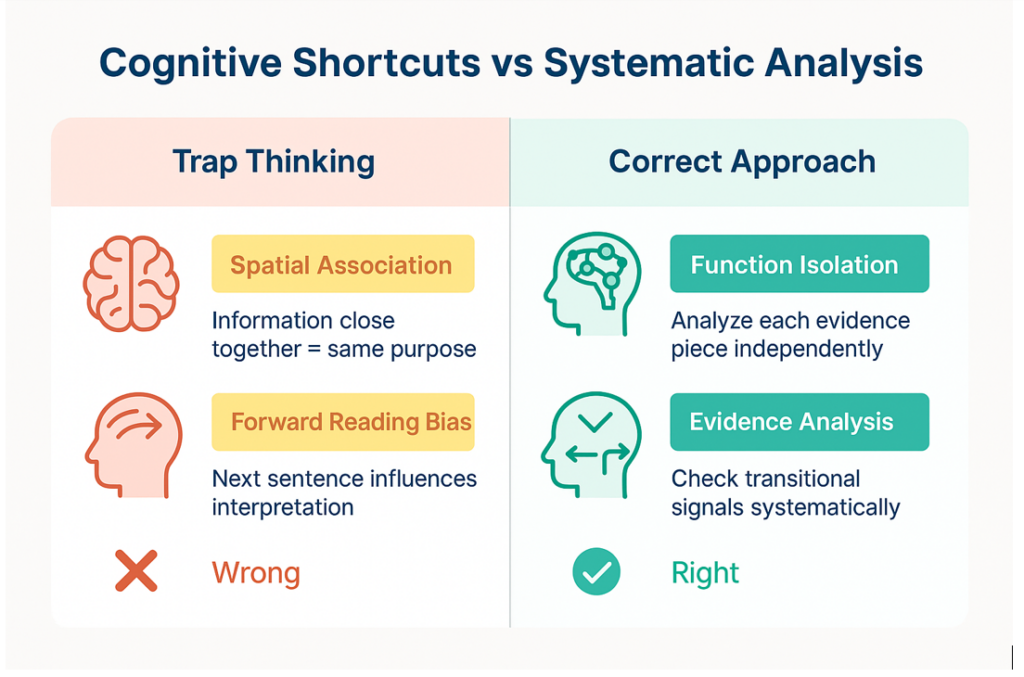

The trap works because of two cognitive shortcuts we naturally employ:

- Spatial Association: Our brains assume that information appearing close together serves related purposes

- Forward Reading Bias: We read the next sentence and unconsciously apply its framework to what we just read

In the exercise passage above, when you read “beyond cardiovascular benefits” immediately after the 20% statistic, your brain wants to categorize that statistic as one of those “beyond” benefits. But the 20% heart function improvement is precisely a cardiovascular benefit—it’s exactly what it claims to be.

The Framework: Evidence Function Analysis

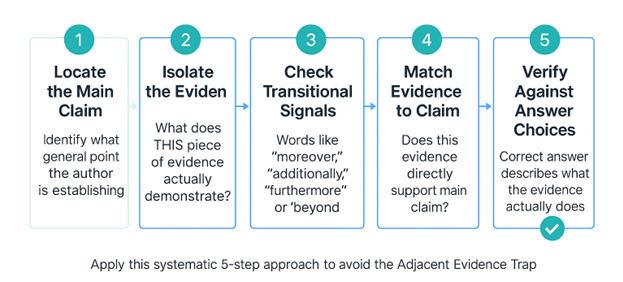

To avoid this trap, use this systematic approach:

- Locate the Main Claim

Identify what general point the author is establishing. Look for broad statements that need support. - Isolate the Evidence

Examine the specific evidence in question. What does THIS piece of evidence actually demonstrate? Read it literally—don’t let nearby sentences influence your interpretation. - Check Transitional Signals

Words like “moreover,” “additionally,” “furthermore,” or “beyond” signal that the author is shifting to a different type of evidence. These markers tell you the function is changing. - Match Evidence to Claim

Ask yourself: Does this evidence directly support the main claim, or does it add something different (extend, qualify, or contrast)? - Verify Against Answer Choices

The correct answer will describe what the evidence actually does, not what nearby evidence does.

Applying the Framework: A Worked Example

Let’s use our simple exercise passage:

“Studies show regular exercise improves cardiovascular health. Research found that participants who exercised three times weekly showed 20% improvement in heart function. Additionally, beyond cardiovascular benefits, exercise improved sleep quality and mental clarity.”

- Step 1 – Main Claim: “Regular exercise improves cardiovascular health”

- Step 2 – Isolate the Evidence: The 20% improvement is specifically about “heart function”—this is cardiovascular

- Step 3 – Transitional Signals: “Additionally” and “beyond cardiovascular benefits” come AFTER the 20% statistic, signaling a shift to different evidence

- Step 4 – Match to Claim: The 20% heart function improvement directly demonstrates cardiovascular health improvement—it supports the main claim

- Step 5 – Verify: Answer A correctly describes this function; Answer B incorrectly applies the purpose of the evidence that comes next

⭐PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

Master the Evidence Function Analysis framework with our comprehensive RC practice questions. Each question comes with detailed explanations showing exactly how to apply this systematic approach.

Practice Exercise 1: Simple Application

Read this passage:

“Historical records indicate that medieval merchants formed guilds to regulate trade. The Wool Merchants’ Guild of Florence, established in 1212, enforced quality standards and set prices. Furthermore, beyond economic regulation, guilds also provided social benefits like funeral assistance and apprentice education.”

Question: The author mentions the Wool Merchants’ Guild primarily to:

- A) Illustrate how guilds regulated trade through specific practices

- B) Demonstrate social functions guilds performed beyond economic regulation

Analysis:

Apply the framework:

- Main Claim: Guilds were formed to regulate trade

- Isolate Evidence: The Florence guild “enforced quality standards and set prices”—these are regulatory/economic functions

- Transitional Signals: “Furthermore, beyond economic regulation” comes after the guild mention

- Match: The guild example demonstrates trade regulation (economic functions), not social benefits

- Answer: A is correct; B describes what the next sentence addresses

Practice Exercise 2: Complex Application

Read this passage:

“Many educators believe standardized testing most reliably measures student achievement because it provides objective data. However, research shows student performance varies with test conditions, and high-scoring students don’t retain information better than others. This view persists among policymakers who’ve inadequately considered classroom-based assessments. In districts implementing portfolio evaluations, learning outcomes improved; one district reported portfolios allowed tracking skill development over time. Moreover, apart from measuring content mastery, portfolio assessments also developed students’ critical thinking abilities.”

Question: The author mentions tracking skill development over time primarily to:

- A) Support a point about portfolio evaluations’ effectiveness

- B) Demonstrate assessment benefits beyond content mastery measurement

Analysis:

- Main Claim: Classroom-based assessments (like portfolios) are more effective than standardized tests

- Isolate Evidence: Tracking skill development over time shows portfolios work well for their intended purpose—measuring learning

- Transitional Signals: “Moreover, apart from measuring content mastery” introduces different evidence

- Match: Skill tracking demonstrates effectiveness at the portfolio’s core function (measuring learning), not additional benefits

- Answer: A is correct; B describes what comes in the “moreover” sentence (critical thinking development)

The Key Insight

The Adjacent Evidence Trap succeeds because it exploits good reading habits—making connections between related information. But on function questions, you must resist the urge to blend adjacent evidence into a single purpose. Instead, recognize that skilled authors layer evidence strategically, with each piece serving a distinct function in building their argument.

When you see transitional markers like “moreover,” “additionally,” or phrases like “beyond” and “apart from,” these are signals that the author is shifting to evidence with a different function. Don’t let this new evidence recolor your understanding of what came before.

⭐ Key Takeaway: In GMAT RC, evidence that appears close together is often functionally distinct. Your job is to identify what each specific piece of evidence actually demonstrates, not what the evidence near it demonstrates.

By applying the Evidence Function Analysis framework systematically, you’ll avoid the Adjacent Evidence Trap and accurately identify why authors include specific details in their passages—a skill that will serve you well beyond test day.

↗️Take Your RC Skills to the Next Level

Ready to master all GMAT RC question types? Access our comprehensive RC strategy course featuring:

- ✅ Complete framework for every RC question type

- ✅ 200+ practice questions with detailed solutions

- ✅ Video lessons breaking down complex passages

- ✅ Timing strategies for maximum efficiency