Here’s what happened to one of my students last week. She was working through an assumption question about ancient Roman mosaics, feeling confident about her approach. The passage described how archaeologists found detailed animal mosaics in the Roman city of Sepphoris, but oddly, most of the animals depicted didn’t actually live in that region. Since identical designs appeared in other Roman cities, the author concluded that traveling artisans must have created them.

“This makes perfect sense,” she told me. “If the same designs show up everywhere, obviously traveling craftsmen made them all.” She quickly selected an answer about the stones used in the mosaics, thinking it supported the traveling artisan theory.

Wrong. And she had no idea why.

The brutal truth? She never asked the one question that changes everything: “What else could explain this exact same evidence?”

Key Takeaways: The Alternative Explanation Framework

Master the critical thinking skill that transforms how you approach assumption questions:

- The “What Else?” Question: Every piece of evidence can support multiple explanations

- Systematic Approach: Generate 2-3 alternative explanations before looking at answer choices

- Pattern Recognition: Assumptions reveal which direction the author chose and what they’re taking for granted

- Real-World Application: This framework improves critical thinking beyond test-taking

The Alternative Explanation Superpower

Here’s what my student missed, and what most students miss: every piece of evidence can usually support multiple explanations. The art of critical thinking isn’t just about following the author’s logic—it’s about systematically generating other ways the same facts could be true.

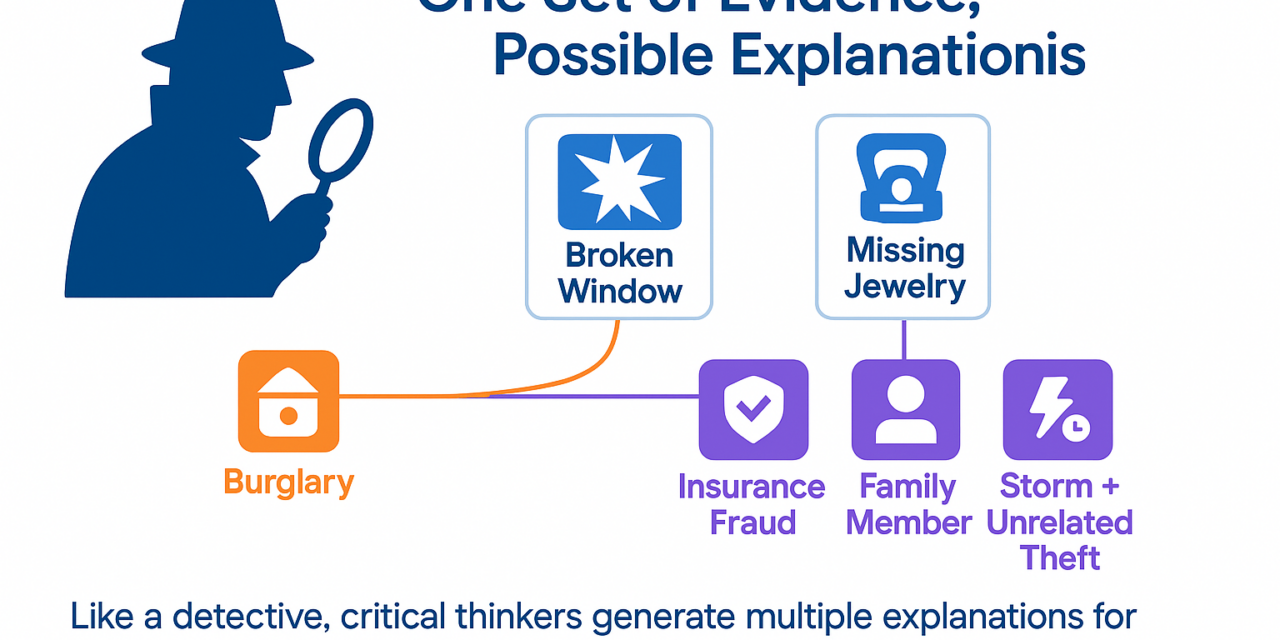

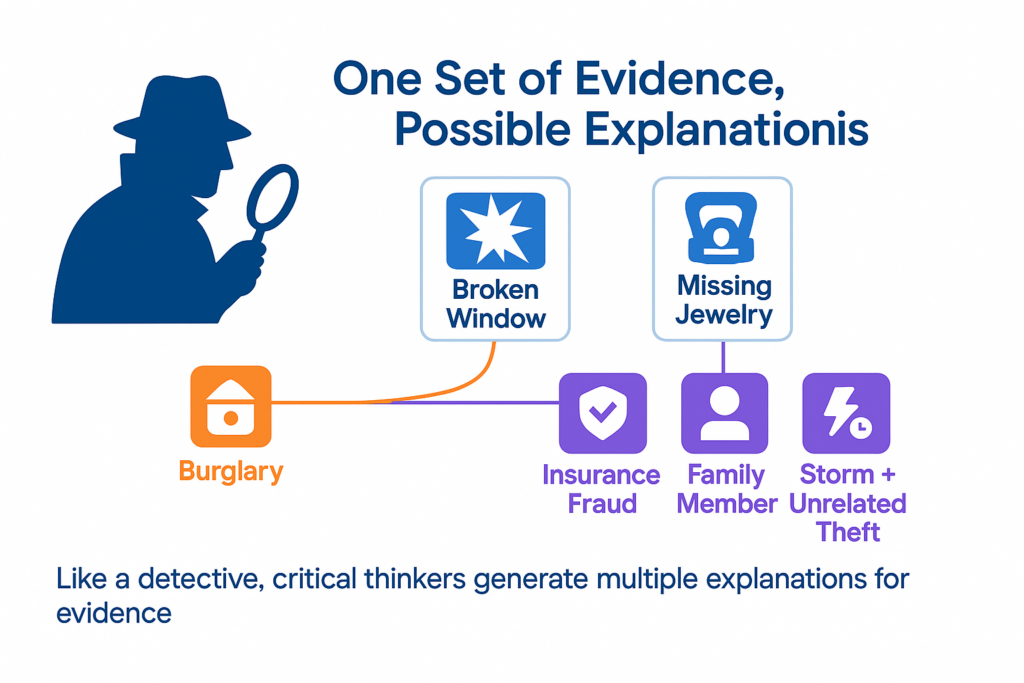

Think about it like being a detective. You walk into a room and find a broken window and missing jewelry. The homeowner immediately says, “It was obviously a burglary!” But a good detective asks: “What are three other explanations for these exact same clues?” Maybe it was insurance fraud. Maybe a family member took the jewelry and staged the break-in. Maybe the window broke from a storm and the jewelry was already missing.

The same evidence, multiple possible explanations.

This is exactly what happens in the hardest verbal reasoning questions. The author presents evidence and draws a conclusion, but there’s almost always an alternative explanation lurking in the shadows.

The “What Else?” Framework in Action

Let me show you how this works with three different types of questions, using the systematic approach that transformed my student’s thinking.

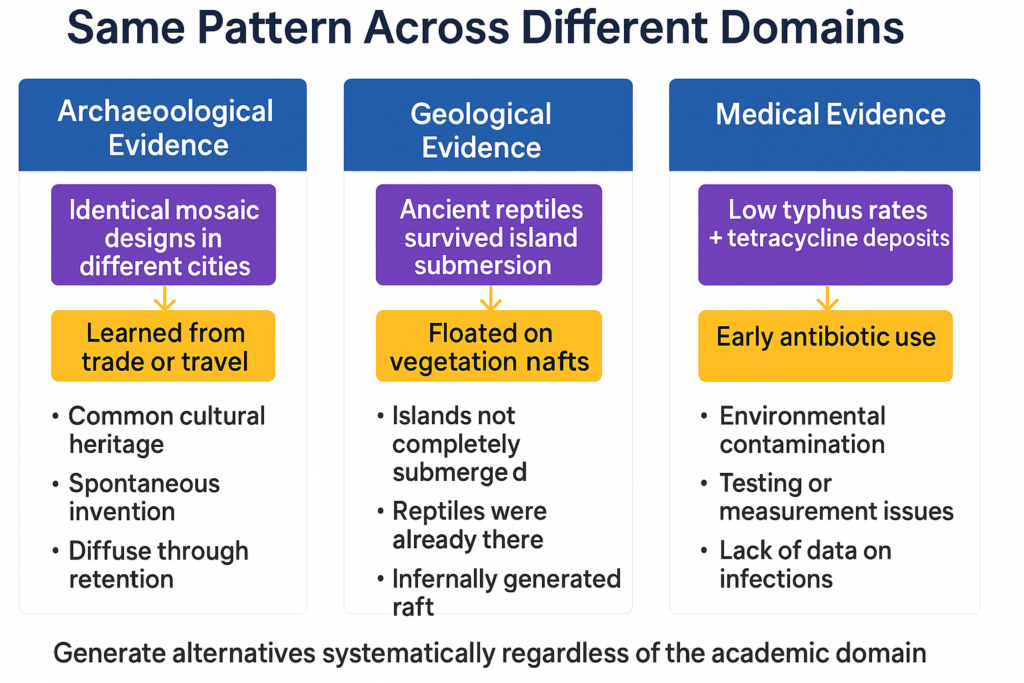

The Archaeological Mystery: Sepphoris Mosaics

The evidence: Identical animal designs appear in mosaics across different Roman cities, showing animals that weren’t native to most of these locations.

Author’s explanation: Traveling artisans created these mosaics, which is why the designs are identical everywhere.

The “What Else?” challenge: Before looking at answer choices, spend 30 seconds generating alternatives:

- What if there was a “design catalog” that all artisans could access?

- What if Roman art schools taught standardized techniques?

- What if there was a common book of mosaic patterns distributed throughout the empire?

Once you generate these alternatives, the assumption becomes crystal clear: the argument depends on there NOT being any shared design resources available to local artisans everywhere. If such resources existed, you wouldn’t need traveling artisans to explain the identical patterns.

The Geological Puzzle: Marlandia’s Surviving Reptiles

The evidence: Modern reptiles on Marlandia islands are descended from ancient reptiles that lived there millions of years ago, even though the islands were supposedly submerged 25 million years ago.

Author’s explanation: Some parts of the islands must have stayed above water during the sea-level rise.

The “What Else?” challenge:

- What if the reptiles could swim between islands during the flooding?

- What if they migrated to other areas and then returned later?

- What if they could survive underwater or on floating debris for extended periods?

The key assumption emerges: the argument depends on these ancient reptiles NOT being able to survive at sea for long periods. If they were excellent swimmers or could live on floating vegetation, they might have survived total submersion.

The Medical Mystery: Nubian Disease Resistance

The evidence: Ancient Nubians had surprisingly low rates of typhus despite living where the disease occurred, and their skeletons contain tetracycline deposits from soil bacteria.

Author’s explanation: Tetracycline in their food protected them from typhus.

The “What Else?” challenge:

- What if the tetracycline got into the bones after they died and were buried?

- What if Nubians had genetic resistance to typhus unrelated to tetracycline?

- What if they had different lifestyle practices that prevented typhus?

The critical assumption: the tetracycline deposits must reflect what living Nubians consumed, not contamination that happened after burial.

The Pattern That Changes Everything

Notice what happens in each case: the same evidence could support completely different conclusions. The author’s explanation isn’t wrong—it’s just not the only possibility. And that’s precisely what assumption questions test.

⭐ The Systematic Approach:

- Read the evidence and conclusion

- Before looking at choices, generate 2-3 alternative explanations for the same evidence

- Ask: “What would have to be true to rule out these alternatives?”

- That’s your assumption

Why This Matters Beyond the Test

This isn’t just a test-taking trick—it’s a life skill. Every day, you encounter people drawing conclusions from evidence: “Sales dropped after we changed the website design, so the new design is terrible!” But what else could explain the sales drop? Seasonal changes? Economic conditions? A competitor’s new product launch?

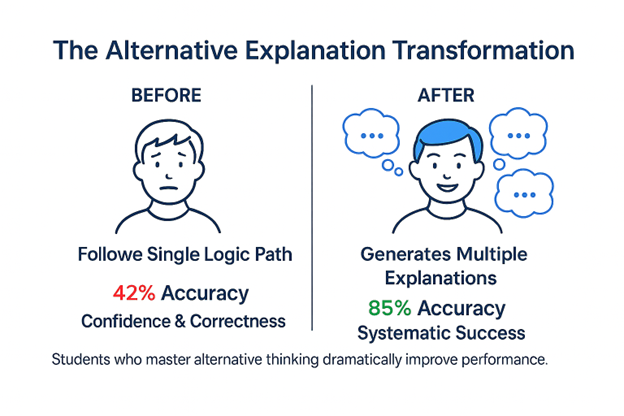

The students who master alternative explanation generation don’t just improve their test scores—they become better critical thinkers in every context.

⭐ Key Insight: The ability to generate alternative explanations transforms both your test performance and your real-world decision-making. Evidence can point in multiple directions, but assumptions reveal which direction the author has chosen—and what they’re taking for granted to get there.

Ready to Build This Superpower?

Here are three official questions that perfectly demonstrate this alternative explanation challenge. Each has an accuracy rate below 55%, but once you understand the systematic approach I just showed you, they become much more manageable.

❓Practice with Purpose:

Question 1: The Sepphoris Mosaic Mystery (Difficulty: 42% accuracy)

Test your ability to generate alternative explanations for archaeological evidence. Look for the assumption that rules out shared design resources.

❓Question 2: The Marlandia Reptile Survival (Difficulty: 38% accuracy)

Practice identifying what must be true about ancient reptiles’ survival capabilities. The alternative explanations you generate will point directly to the assumption.

❓Question 3: The Nubian Tetracycline Protection (Difficulty: 47% accuracy)

Challenge yourself to distinguish between ancient consumption and post-burial contamination. Your systematic alternative thinking will unlock this medical mystery.

Next Week: Strategic Implementation

Once you’ve mastered generating alternative explanations, you’ll be ready for next week’s article: “Strategy vs. Reality: When Plans Ignore Implementation Challenges.” We’ll take this same systematic thinking and apply it to business strategy questions, where the ability to generate alternative outcomes becomes crucial for identifying what could go wrong.

➡️ Remember: The examples I used throughout this article are based on these three official questions. Evidence can point in multiple directions, but assumptions reveal which direction the author has chosen—and what they’re taking for granted to get there.