Here’s a question that reveals everything about how you think: If someone argues that a restaurant should close because “the health inspector found violations, and customer safety must come first,” which principle supports their reasoning better?

A) “Restaurants with health violations should be closed.”

B) “When a business practice threatens what must be prioritized, that practice should stop.”

Most test-takers pick A instantly. It matches the conclusion perfectly. But the arguer’s actual logic—priority conflict requires action—is captured only by B. This gap between supporting a conclusion and supporting the reasoning behind that conclusion is where over 60% of test-takers fail on official GMAT principle questions.

Key Takeaways from This GMAT Principle Strategy:

Understanding GMAT principle questions requires recognizing a crucial distinction:

- Most test-takers focus on supporting the conclusion

- High scorers focus on supporting the reasoning process

- The gap between these approaches determines success on 60%+ of principle questions

This guide provides a systematic framework to identify principles that validate the arguer’s actual logical pathway.

⭐MASTER CRITICAL REASONING STRATEGIES

Ready to go beyond surface-level CR practice? Access our comprehensive Critical Reasoning course with detailed strategic frameworks, 200+ practice questions, and expert video explanations.

The Cognitive Trap: Confusing Position with Process

Consider this scenario:

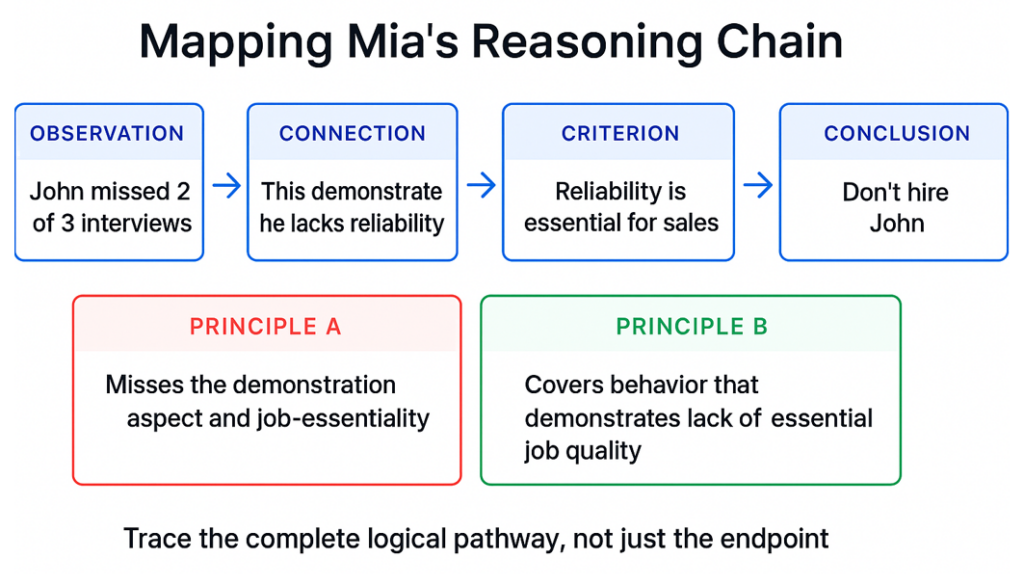

Mia argues: “We shouldn’t hire John for the sales position. He missed two of his three scheduled interviews, and in sales, reliability is everything. His interview absences show he lacks the reliability we need.”

Which principle best supports Mia’s reasoning?

Principle A: “Candidates who demonstrate unreliability during the hiring process should not be hired.”

Principle B: “If a candidate’s behavior during hiring demonstrates they lack an essential job quality, they should not be hired.”

Most people choose Principle A because Mia wants to reject John, and Principle A says unreliable candidates shouldn’t be hired. Perfect match, right?

Wrong. Mia isn’t just saying “John is unreliable, so reject him.” Her specific reasoning follows this path: “The interview absences demonstrate he lacks reliability, and reliability is essential for this specific role.” Principle B captures this complete reasoning chain—behavior demonstrates a lacking quality that’s job-essential. Principle A only addresses where her logic ends up, ignoring the crucial connections she actually made.

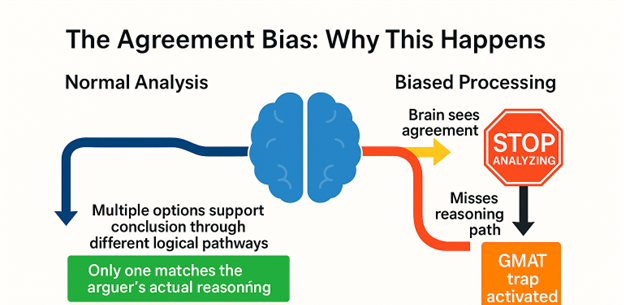

Why This Happens: The Agreement Bias

When we see a principle that agrees with an argument’s conclusion, our brains deliver a satisfying click of alignment. We stop analyzing. We fail to ask: “Does this principle support the specific path the arguer took to reach that conclusion?”

⭐ Key Insight: GMAT test-makers exploit this by including multiple options that support the conclusion through different logical pathways. Only one matches the arguer’s actual reasoning. The others are sophisticated traps—same destination, different route.

The Framework: The Reasoning-Match Process

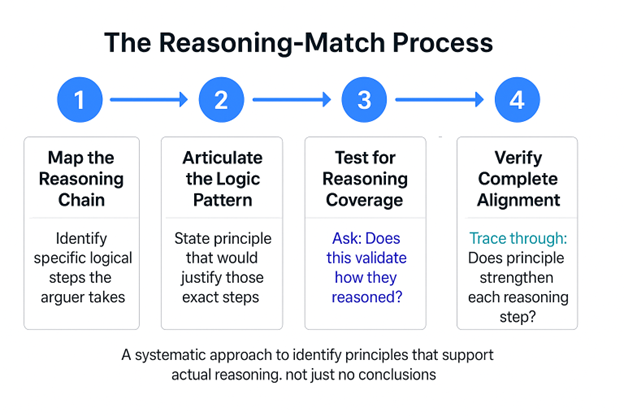

To identify principles that support the actual reasoning (not just the conclusion), follow this systematic approach:

- Map the Reasoning Chain

Identify the specific logical steps the arguer actually takes. Don’t summarize their conclusion; trace their journey. Ask: “What specific connections does this person make? What criteria do they invoke?” - Articulate the Logic Pattern

Before looking at answer choices, state in your own words what principle would justify those exact logical steps. Example: “If X demonstrates Y, and Y is essential for Z, then…” This pre-commitment prevents seduction by attractive-but-wrong options. - Test for Reasoning Coverage

For each answer choice, ask: “Does this principle validate how they reasoned, or just what they concluded?” The correct answer bridges the specific gaps in their argument, not just endorses their endpoint. - Verify Complete Alignment

Trace through the logic: “If I accept this principle as true, does it strengthen each step of the arguer’s reasoning?” The principle should support the connections, not just the conclusion.

Applying the Reasoning-Match Process

Let’s apply this to our earlier example:

Mia’s Argument: “We shouldn’t hire John for the sales position. He missed two of his three scheduled interviews, and in sales, reliability is everything. His interview absences show he lacks the reliability we need.”

Step 1: Map the Reasoning Chain

- Observation: John missed interviews

- Connection: This demonstrates he lacks reliability

- Criterion: Reliability is essential for sales

- Conclusion: Therefore, don’t hire him

Step 2: Articulate the Logic Pattern: “If someone’s behavior during hiring demonstrates they lack a quality that’s essential for the specific job, they shouldn’t be hired.” Note the three elements: behavioral demonstration + essential quality + job-specific.

Step 3: Test for Reasoning Coverage:

- Principle A covers “unreliability → don’t hire” but misses the demonstration aspect and the job-essentiality criterion

- Principle B covers “behavior demonstrates lacking of essential job quality → don’t hire” ✅

Step 4: Verify Complete Alignment: If Principle B is true → Mia’s connection from “missed interviews” to “demonstrates lack of essential quality” is validated → her conclusion is strongly supported. ✅

Answer: Principle B

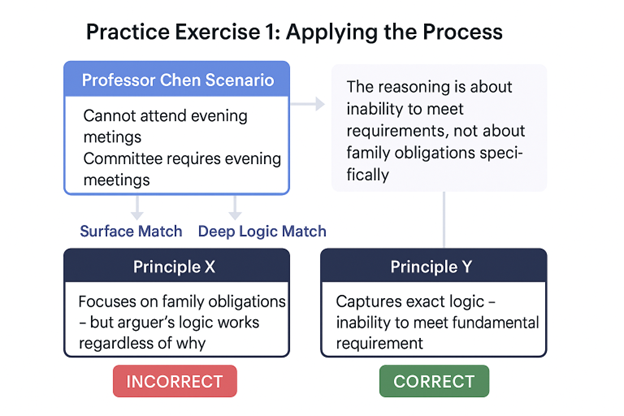

⚡PRACTICE EXERCISE 1: SIMPLE APPLICATION

Argument: “Professor Chen shouldn’t lead the research committee. The committee requires evening meetings, and Professor Chen explicitly stated she cannot attend evening meetings due to family obligations.”

Which principle best supports this reasoning?

Principle X: “People with family obligations should not be given leadership roles that conflict with those obligations.”

Principle Y: “If someone cannot fulfill a fundamental requirement of a role, they should not be given that role.”

Apply the Reasoning-Match Process before reading the analysis below.

Analysis:

Map the Chain: Cannot meet fundamental requirement (evening attendance) → Should not get role.

Principle X focuses on family obligations causing conflict—but the arguer’s logic works regardless of why she can’t attend. The reasoning is about inability to meet requirements, not about family obligations specifically.

Principle Y captures the exact logic: inability to meet fundamental requirement → should not get role.

Answer: Principle Y

Notice how Principle X includes elements from the argument (family obligations, leadership role), but it doesn’t match the actual reasoning structure.

⚡PRACTICE EXERCISE 2: COMPLEX APPLICATION

Two Managers Debate a Policy:

“Company policy states: ‘Employees who arrive late three times in one month will receive a formal warning.’ Sarah has arrived late three times this month.

Manager P: We should issue the formal warning to Sarah. She’s aware of the policy, and she chose to take a route to work that she knew was unreliable. Her lateness was within her control.

Manager Q: While Sarah technically violated the policy, issuing a formal warning would damage team morale since she’s been covering extra shifts. We should address her lateness through informal coaching instead.”

Principles:

- “Employees who can control their compliance with a policy but fail to do so should receive the specified consequence.”

- “Policy consequences should always be applied to ensure all employees are treated the same way.”

- “If applying a specified policy consequence would harm the broader organization, an alternative response should be used.”

- “The consequences for policy violations should be determined by the organization’s needs rather than by the specified policy consequences.”

- “Employees who provide extra value to an organization should not receive formal warnings.”

Question: Select one principle that supports Manager P’s reasoning and one that supports Manager Q’s reasoning.

Apply the Reasoning-Match Process to each manager before checking the analysis below.

Analysis:

Manager P’s Reasoning Chain:

- Sarah aware of policy + chose unreliable route = had control

- Had control over compliance → should get specified consequence

Best Match: Principle 1 (explicitly connects “control” to “specified consequence”)

❌ Reject Principle 2: Supports the conclusion (issue warning) but through different reasoning (equal treatment, not control)

Manager Q’s Reasoning Chain:

- Acknowledges policy violation + formal warning would harm morale

- Harm to organization → use alternative approach instead

Best Match: Principle 3 (connects specified consequence + organizational harm + alternative)

❌ Reject Principle 4: Too broad; doesn’t specifically address when to use alternatives

❌ Reject Principle 5: Focuses on value contribution rather than organizational harm

Answers: Manager P = Principle 1; Manager Q = Principle 3

The Ultimate Distinction

The highest-scoring test-takers understand this: In principle questions, you’re not selecting what supports the speaker’s conclusion—you’re selecting what validates their specific logical pathway.

Every time you evaluate a principle option, ask: “Does this principle justify the exact connections this person made, or just their endpoint?” That single question, applied rigorously, transforms your performance.

⭐ Key Takeaway: The path matters more than the destination. Make sure your selected principle walks the same path your arguer walked—not just arrives at the same place.

⭐ Master All Critical Reasoning Question Types

Ready to apply these precise reasoning strategies across all CR question types? Get comprehensive training with:

- ✅ Strategic frameworks for all 10+ CR question types

- ✅ 200+ practice questions with detailed explanations

- ✅ Video lessons breaking down complex reasoning patterns

- ✅ Personalized practice and progress tracking