Variance analysis is a sure shot test to verify that you have chosen the correct answer for “Evaluate the argument” question types. In this article, we will discuss the theory of Variance analysis, talk about how to apply the test through various examples, and solve multiple exercise questions.

What is Variance Analysis?

By definition, the correct answer choice to evaluate an argument will either increase or decrease the validity of the argument. By performing the variance analysis, we can see whether an answer choice does that. In other words, test exploits the duality or the dual behavior of the correct answer choice.

Those of you who read my earlier article on the negation test (or are in general aware of the same) will see some parallels with the negation test. However, there is a stark difference between the two.

The negation test, when applied on the correct answer choices (or the assumption) breaks the argument down, whereas the variance analysis when performed on the correct answer choice goes both ways – validates the argument (makes the argument much more believable) and invalidates the same (i.e. breaks the argument/destroys the argument).

How to apply this test?

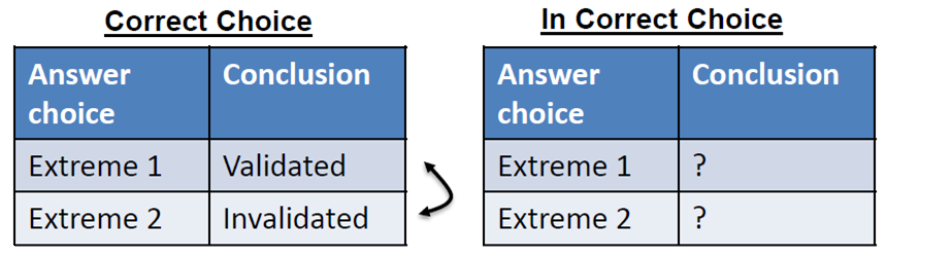

To apply this test to a particular answer choice, take that answer choice to one extreme. Let’s call this extreme 1. Notice the impact on the conclusion of the argument. Then take the answer choice to the other extreme, extreme 2, and notice the impact on the conclusion again. If extreme 1 validates the argument and extreme 2 invalidates the argument or vice versa, then this is the correct answer choice. If the argument is only validated or invalidated at one of the extremes and nothing happens to it at the other extreme then this is not the correct choice.

Note that extremes usually fall in two categories;

- High/low

- Yes/No

The examples and exercise questions below will help you practice both the extremes.

Let’s take an example:

Simple example:

Joshua is one of the most thanked members on GMATClub. Hence, Joshua will most likely score above 700 on his GMAT.

Which of the following below would help you evaluate the argument above?

- Whether all GMATClub members who score above 700 receive at least one thanks.

- Whether, Rosy, another member who was one of the most thanked members on GMATClub, scored above 700 or not.

- Whether Joshua scored more than 700 in his most recent mock test?

- Whether most GMATClub’s most thanked members score above 700.

- Whether Joshua received the “most thanked” status by being active on just the quant forum or both quant and verbal forum.

- Whether GMATClub members who are not rated “most thanked” are as likely to score above 700 as those who are?

Now let’s take each answer choice and evaluate it. But before we do that lets understand what the argument is saying. The argument states that Joshua has a greater than 50% (note: most likely = greater than 50%) chance of scoring above 700 because he is one of the “most thanked” members on GMATClub.

- Choice A: Whether all GMATClub members who score above 700 receive at least one thanks?

- Extreme 1: Yes, All GMATClub members who score above 700 receive at least one thanks.

Does this validate the argument? No it does not. What extreme1 says is that if you are a GMATClub member who had scored above 700, then you must have received one thanks. This has no bearing on the conclusion which says that if you are the most thanked member, you have greater than 50% chance to score 700. Hence this extreme neither validates nor invalidates the argument. At this point, you may leave this choice and go to choice 2. However we will analyze extreme 2 for academic fun.

- Extreme 2: No, All GMATClub members who score above 700 do not receive at least one thanks?

Using the same logic as above, it can be said that this extreme has no bearing on the conclusion. Hence let’s move on to choice B.

- Choice B: Whether, Rosy, another member who was one of the most thanked members on GMATClub, scored above 700 or not.

- Extreme 1: Yes, Rosy, another member who was one of the most thanked members on GMATClub, scored above 700.

Does that strengthen the conclusion – yes, because we have one more instance in which the conclusion is true. However, does this validate the conclusion – No. Therefore, this choice is not the correct choice.

- Choice C: Whether Joshua scored more than 700 in his most recent mock test?

- Extreme 1: Yes, Joshua scored more than 700 in his most recent mock test.

This is another choice that strengthens the argument but does not either validate or invalidate the argument. Note, that this extreme would increase our belief in the conclusion that Joshua is likely to score above 700 in the real test but not because of the reasons stated in the argument, which is what we are evaluating right now. Hence, it does not validate the author’s argument.

- Extreme 2: No, Joshua did not score more than 700 in his most recent mock test.

Similarly, the fact that Joshua did not perform as well on the mock does not invalidate the argument that Joshua has greater than 50% chance of scoring above 700.

- Choice D: Whether most GMATClub’s most thanked members score above 700?

- Extreme 1: Yes, most GMATClub’s most thanked members score above 700?

This validates the argument. Notice, that the while claiming that Joshua is most likely to score above 700 because he is one of the most thanked members, the author assumes that most of the “most thanked” members score above 700. Extreme 1, validates that assumption thereby validating the argument.

- Extreme 2: No, most GMATClub’s “most thanked” members do not score above 700?

This invalidates the argument. Note how “Extreme 2” breaks the argument. If most “most thanked” members do not score above 700 then there is no reason to believe that Joshua will score above 700.

Due to this bipolar nature exhibited by this answer choice, we can easily say that this is the correct answer choice.

- Choice E: Whether Joshua received the “most thanked” status by being active on just the quant forum or both quant and verbal forum?

- Extreme 1: Yes, Joshua received the “most thanked” status by being active on just the quant forum?

Does this validate or invalidate the argument. It does neither. Note that the author does not state whether those “most thanked” members who score above 700 are active just on quant or verbal or on both forums. Since the author does not make any such claim, the answer to choice E does not validate or invalidate the argument.

- Choice F: Whether GMATClub members who are not rated “most thanked” are as likely to score above 700 as those who are?

E-GMAT customers would instantly reject this answer choice because this talks about a segment of population that is not the focus of the argument. This answer choice talks about those members who are not rated as “most thanked”, something that has little bearing on the point that the argument is trying to make. Therefore, this choice is not correct.

Question: Can you modify the argument to make this choice relevant?

TAKEAWAYS FROM THE EXAMPLE ABOVE

- A choice that just strengthens need not be the correct choice: A number of people have this notion that validation is the same as strengthening. As we saw with choice B such is not the case. While a choice that validates the argument will strengthen it, the converse need not be true.

- The correct choice is built around the Assumption: This must now be intuitive. An argument is validated only if one or more of the assumptions that the author makes are validated in some form. E-GMAT customers would recall the Joshua example, from Evaluate Concept in e-GMAT CR Course, in which we derive 3 possible evaluate answer choices from a single assumption. This means that the Prethinking process for assumptions that we learned in the Prethinking Session is highly useful in helping you solve evaluate questions as well.

- The variance analysis is a close cousin of Negation test: The negation test when applied on the correct answer choice breaks the argument (invalidates the argument), while the correct answer choice either validates or invalidates. The fundamental principle governing both these tests is the same – an argument has assumptions, which when negated can invalidate the argument.

EXERCISE QUESTIONS:

Below are two exercise questions. Apply the variance test to these questions to test whether you can successfully apply the test to questions to arrive at the correct answer.

Exercise 1 (Source OG)

Although custom prosthetic bone replacements produced through a new computer-aided design process will cost more than twice as much as ordinary replacements, custom replacements should still be cost-effective. Not only will surgery and recovery time be reduced, but custom replacements should last longer; thereby reducing the need for further hospital stays.

Which of the following must be studied in order to evaluate the argument presented above?

(A) The amount of time a patient spends in surgery versus the amount of time spent recovering from surgery

(B) The amount by which the cost of producing custom replacements has declined with the introduction of the new technique for producing them

(C) The degree to which the use of custom replacements is likely to reduce the need for repeat surgery when compared with the use of ordinary replacements

(D) The degree to which custom replacements produced with the new technique are more carefully manufactured than are ordinary replacements

(E) The amount by which custom replacements produced with the new technique will drop in cost as the production procedures become standardized and applicable on a larger scale

Exercise 2 (Source GMATPrep)

The Nile Delta of Egypt was invaded and ruled from 1650 BC to 1550 BC by a people called Hyksos. Their origin in uncertain but archaeologists hypothesize that they were Canaanites. In support of this hypothesis, the archaeologists point out that excavations of Avaris, the Hyksos capital in Egypt, have uncovered large number of artifacts virtually identical to artifacts produced in Ashkelon, a major city of Canaan at the time of the Hyksos invasion.

In order to evaluate the force of the archaeologists evidence, it would be most useful to determine which of the following?

- Whether there were some artifacts found at Avaris that were unlike those produced in Ashkelon but that date to before 1700 BC.

- Whether the Hyksos ruled any other part of Egypt besides the Nile Delta in the period from 1650 B.C. to 1550 B.C.

- Whether Avaris was the nearest Hyksos city in Egypt to Canaan.

- Whether Ashkelon after 1550 B.C. continued to produce artifacts similar to those found at Avaris.

- Whether many of the artifacts found at Avaris that are similar to the artifacts produced in Ashkelon date to well before the Hyksos invasion.